It's A Battle To The Death In USVI Waters Between Some Corals And Sponges

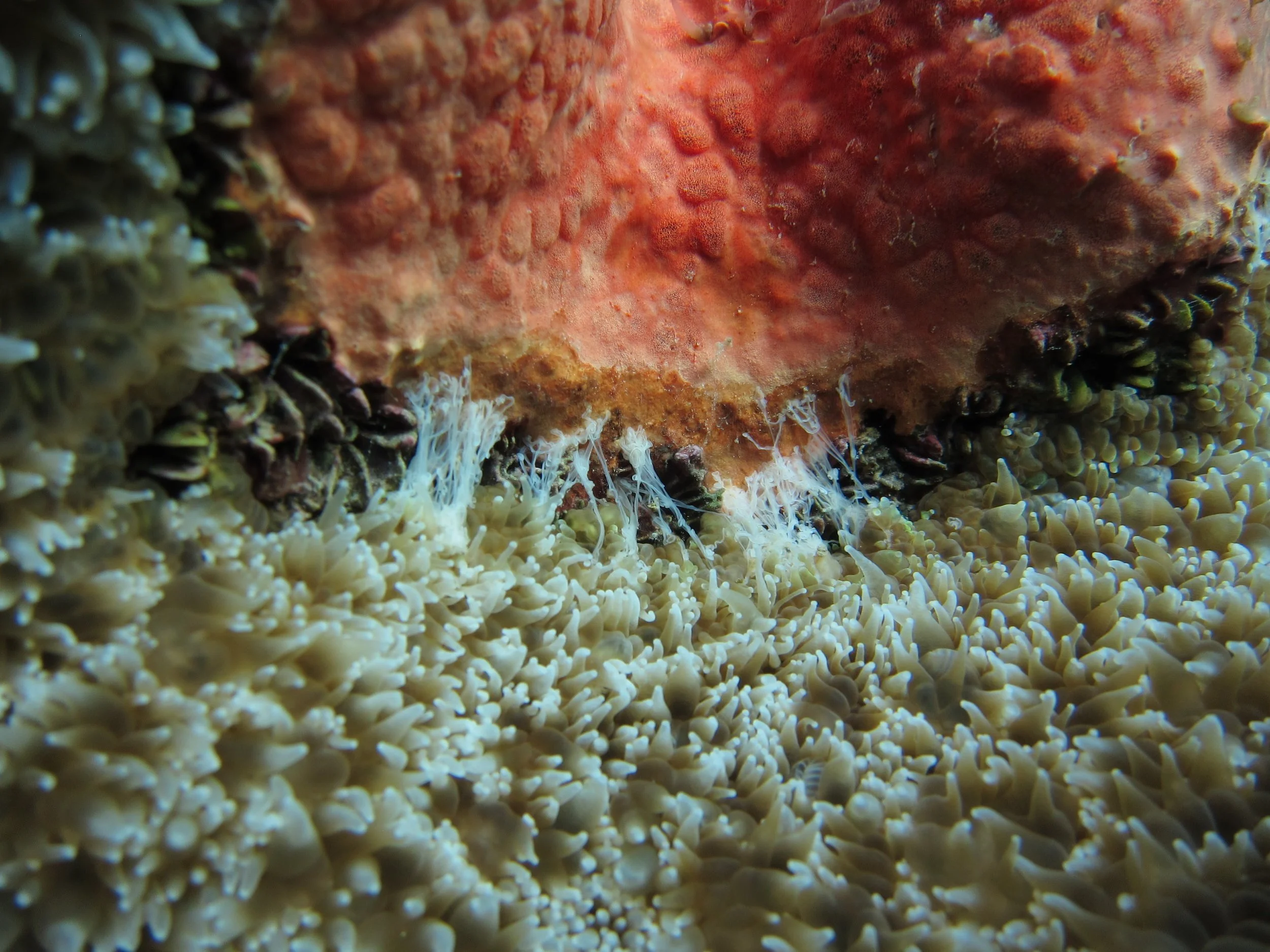

The succession seen here shows how a coral colony can be overpowered by a growth of Cliona delitrix sponge (top picture). We can also see when both coral and sponge die resulting in the colony being covered by algae.

Photos provided by Sven Zea and Andia Chaves-Fonnegra

vi-epscor –supported researcher at the university of the virgin islands publishes important findings on coral stress in a major scientific journal

Just one day before Hurricane Irma, Global Change Biology accepted for publication the article Bleaching Events Regulate Shifts From Corals to Excavating Sponges in Algae Dominated Reefs, submitted by Andia Chaves-Fonnegra, Postdoctoral Research Associate at UVI's Center for Marine and Environmental Studies.

This work was co-authored and supported by Bernhard Riegl, Nova Southeastern University, Florida, Sven Zea, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Jose V. Lopez, Nova Southeastern University, Florida, Tyler Smith, University of the Virgin Islands, Marilyn Brandt, University of the Virgin Islands, and David S. Gilliam, Nova Southeastern University, Florida.

Cliona delitrix, seen above, is a bright orange sponge which uses enzymes to dissolve the coral skeleton it lives on and burrows into it. Until now, little research has been done to examine the growth and effects of this sponge after coral bleaching events.

Dr. Chaves-Fonnegra and her team examined the relationship between excavating sponges and their coral substrate. Of particular interest was Cliona delitrix, a burrowing encrusting sponge. Cliona tends to grow on and cover over larger-bodied corals. It is sometimes found on calcareous substrates such as a shell or a limestone rock (it does not, however, grow on branching corals). Cliona produce enzymes which are used to dissolve the coral skeleton and burrow into it.

The team created models to provide data on the response of these excavating sponges after bleaching events. Among the coral colonies monitored for over eleven years were 271 corals in St. Croix, USVI. Findings show that excavating sponge abundance was greater in St. Croix than the other locations after bleaching events and that even healthy corals were impacted from interaction with Cliona. The other monitored corals were in San Andres Island, Colombia and Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

after bleaching events, excavating sponge abundance was greater in St. Croix than the other monitored locations

Results show that increased stress on corals, including warming water temperatures, create conditions conducive to excavating sponge growth. Their success also depends on the intensity of coral stress. As Caribbean coral reefs are expected to experience greater and greater stress from human development and warming ocean temperatures, it is important to be able to distinguish changes on reefs that are natural from those that may be driven by large disturbances such as bleaching events. This research is therefore critical as it demonstrates that Cliona delitrix, an easily identifiable sponge species, can be a reliable indicator of recent disturbances on Caribbean coral reefs.

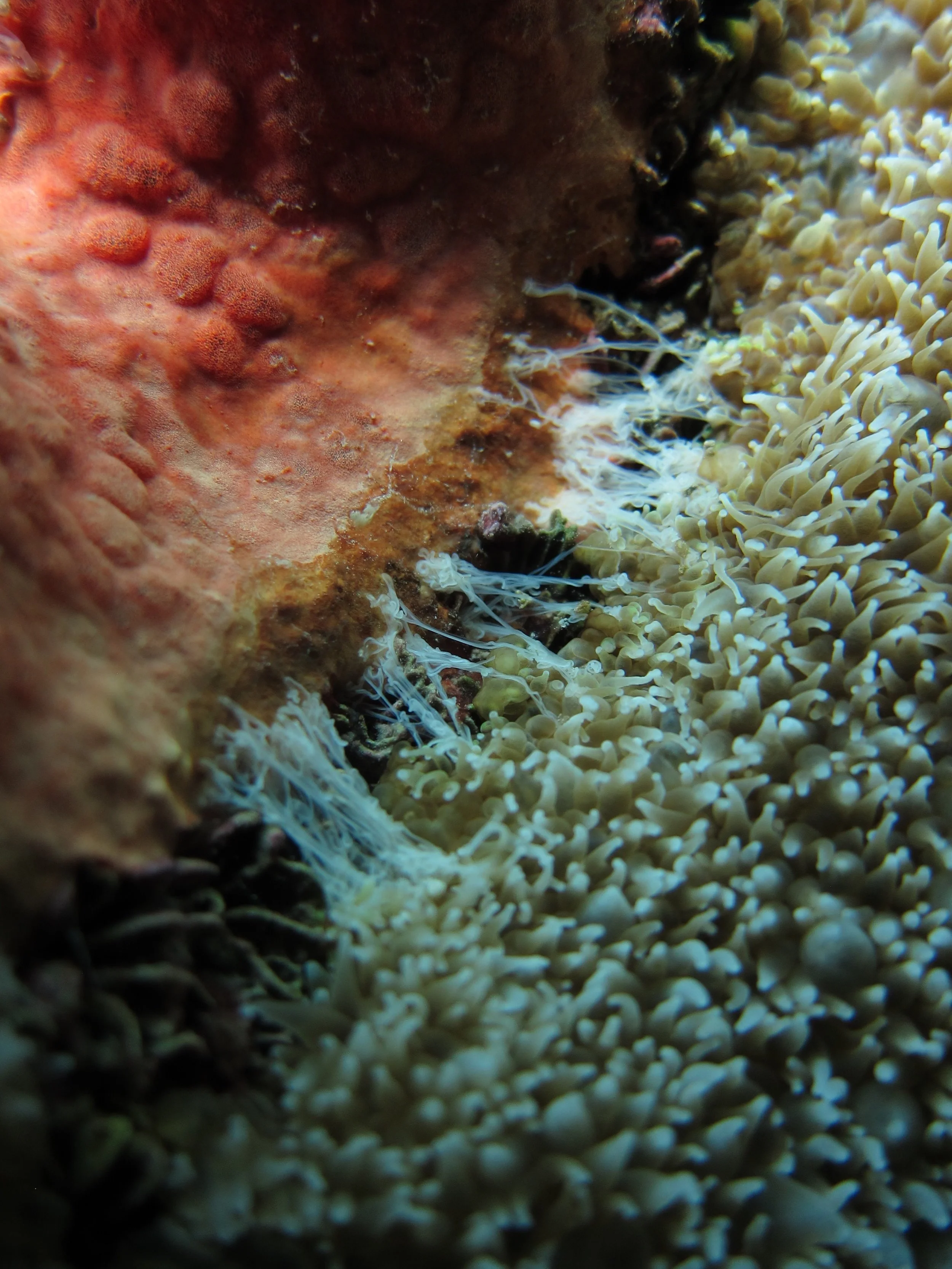

Photo by Dr. Chaves-Fonnegra

Photo by Dr. Chaves-Fonnegra

As seen above, corals use mesenterial filaments (white) to attack the sponge (orange). Mesenterial filaments are a coral's attempt to attack and digest invaders or competitors.

published ABSTRACT

Changes in coral-sponge interactions can alter reef accretion/erosion balance and are important to predict trends on current algal-dominated Caribbean reefs. Although sponge abundance is increasing on some coral reefs, we lack information on how shifts from corals to bioeroding sponges occur, and how environmental factors such as anomalous seawater temperatures and consequent coral bleaching and mortality influence these shifts. A state transition model (Markov chain) was developed to evaluate the response of coral excavating sponges (Cliona delitrix Pang 1973) after coral bleaching events. To understand possible outcomes of the sponge-coral interaction and build the descriptive model, sponge-corals were monitored in San Andres Island, Colombia (2004-2011) and Fort Lauderdale, Florida (2012-2013). To run the model and determine possible shifts from corals to excavating sponges, 217 coral colonies were monitored over 10 years (2000-2010) in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, and validated with data from 2011 to 2015. To compare and test its scalability, the model was also run with 271 coral colonies monitored in St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands over 11 years (2004-2011), and validated with data from 2012-2015. Projections and sensitivity analyses confirmed coral recruitment to be key for coral persistence. Excavating sponge abundance increased in both Fort Lauderdale and St. Croix reefs after a regional mass bleaching event in 2005. The increase was more drastic in St. Croix than in Fort Lauderdale, where 25% of the healthy corals that deteriorated were overtaken by excavating sponges. Projections over 100 years suggested successive events of moderate coral mortality could shift algae-coral dominated reefs into algae-sponge dominated. The success of excavating sponges depended of the intensity of coral bleaching and consequent coral mortality. Thus, the proportion of Cliona delitrix excavating sponges is a sensitive indicator for the intensity and frequency of recent disturbance on Caribbean coral reefs.

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.