Nassau Grouper In The U.S. Virgin Islands: A Story Of Recovery And Treachery

Written by Elisa Bryan. Photos and captions by Dan Mele.

Dr. Rick Nemeth at the University of the Virgin Islands has been studying the endangered Nassau grouper for over 20 years in the US Virgin Islands. Nassau Grouper, once plentiful, are now very rare in the USVI territory and throughout the Caribbean. The timeline of how this once thriving species finds itself on the brink of extinction is a sad yet not uncommon story.

Caribbean families have sustained themselves by fishing for generations. Surrounded by the gorgeous Caribbean Sea, there is a natural relationship with the ocean as a source of sustenance and livelihood. Nassau Grouper are a local favorite and were once a regular addition to the dinner table. In St. Thomas, a dramatic decline in the Nassau population was documented in 1978. By the early 1980s, they became 'commercially extinct,' indicating that it was no longer economical to fish for this species.

This decline can be directly linked to the discovery of their spawning aggregations. To grasp the significance of this discovery, it’s helpful to understand how the Nassau, and many other fishes, breed.

Dr. Richard Nemeth, Ridge to Reef Co-PI, Fish Ecology Lead Researcher, and UVI Research Professor of Zoology & Marine Biology.

Shaun Kadison, Research Analyst at the University of the Virgin Islands, has been working closely with Dr. Nemeth since 2003, and has been fundamental to these research efforts.

Spawning Events

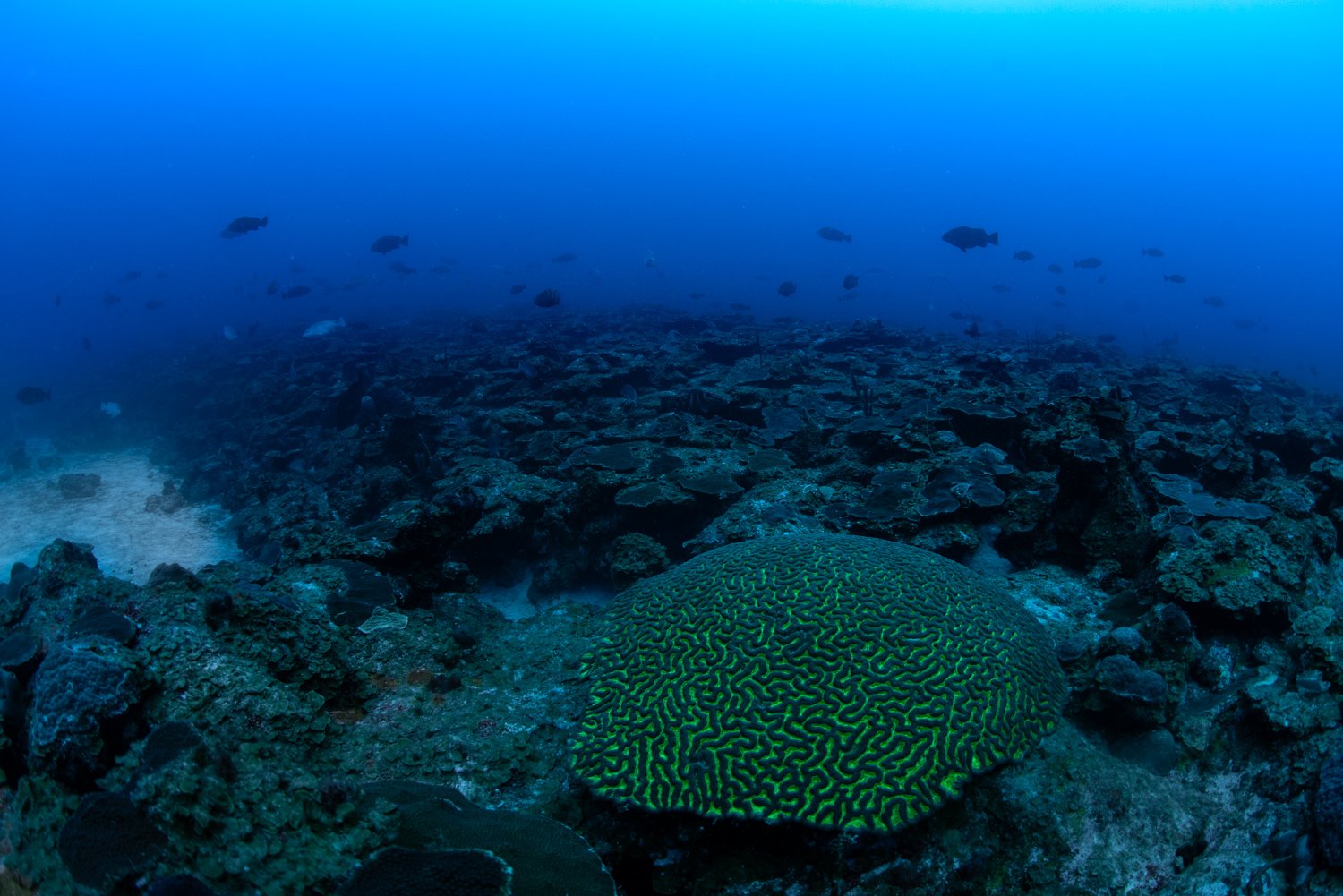

Certain fish species gather en masse at regular, predictable times for the purpose of reproduction. These gatherings, which is always at the same location, are known as spawning aggregations. While not all fish reproduce this way, most economically important species do. This includes groupers, snappers, triggerfish, parrotfish, surgeonfish, and many others. Spawning aggregations can attract anywhere from hundreds to thousands or even tens of thousands of a single fish species at one time. Between having large numbers in one location, and the fishes’ intense focus on reproducing, the aggregating species are very vulnerable to predation by large fish like sharks, barracuda, kingfish and almaco jacks and especially humans.

Once fishermen discovered the grouper’s spawning aggregations and learned their very predictable spawning schedule, concentrated fishing, even wasteful overfishing, led to collapsed fisheries throughout the Caribbean. For a fisherman, the discovery of a spawning aggregation was like winning the lottery: a lot of money could be made very quickly. In essence, heavy fishing meant most adults of the species were harvested before spawning and all their potential offspring were eliminated in one deadly swoop. In fact, so many Nassau were caught in the 70s and 80s that the market was over-saturated. Fishermen couldn’t sell them fast enough so whatever remained at the end of the day was discarded. Fishermen simply caught more the next day...and the next. Today, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists Nassau grouper as a critically endangered species but, we don’t need the IUCN to tell us...we can see this for ourselves every time we go to market or fish recreationally. Nassau grouper are now better known because of their absence in the fish pots and on the reefs.

Dr. Rick Nemeth and Shaun Kadison have been diving the Grammanik Bank for over two decades. They’ve spent several hundred to over a thousand hours underwater at this site over the course of their careers.

Signs Of Hope

One fortuitous day in 2005, the startling discovery of a small aggregation of about fifty Nassau grouper was spotted on the Grammanik Bank, about 12 miles south of St. Thomas. Dr. Nemeth investigated and quickly alerted the National Marine Fisheries Service. Until this discovery, it was believed that Nassau grouper no longer spawned in USVI waters at all. Nemeth recommended the site be closed and, after much negotiation, a protected boundary of 1.5 km was established. (Despite new research demonstrating why the protected area should be expanded significantly, it remains the same size today.) Closure of the Grammanik Bank seasonally to fishing was met with great controversy and push-back from the community but over the past 10 years, sightings of Nassau grouper on reefs around St. Thomas and St. John have increased significantly. Seasonal closure has demonstrably allowed the Nassau grouper population to increase steadily, enough so that during the 2024 spawning season, more than 1,000 Nassau grouper were counted! This is a tremendous accomplishment, particularly as numbers continue to decline in other areas throughout the Caribbean. Belize for example is showing no signs of recovery to their Nassau grouper populations. The Bahamas experienced the collapse of an aggregation by 2002 and a second very large aggregation was completely wiped out by 2013. The entire population crashed in Bermuda by 1981 with no signs of recovery since. The 1,000 Nassau counted may seem like a lot of fish, but not when you consider that an estimated 10,000 Nassau grouper used to aggregate before the population was fished out over 40 years ago.

It is therefore not an understatement to say that it is a rare and special treat to see a juvenile Nassau on the reef when snorkeling or diving. Some would argue that this means the species has recovered and fishing should be permitted again but, no. Recovery is slow yet steady. In the 18 years since the closure scientists have seen intermittent surges of rapid increase, or “pulses”, in numbers. A pulse occurred once in 2009 and again in 2015. Juveniles started to settle in 2009 and began appearing as reproductive adults by 2012 - 2014. By 2015 there was an even larger pulse of juveniles settling around the territory. Today, we are just beginning to see them arriving at the spawning site.

Nothing lives in isolation. When large groupers and snapper were eliminated from the food chain there was a release of predation on their food source. As a result, smaller predators increased in number which caused a decrease in their food supply and affected their habitats in unforeseen ways. One example of this are damselfish. These pretty little fish live within coral crevices and only large grouper with their powerful suction feeding technique are able to pull them out. When large groupers disappeared, damselfish were free to live on top of the coral, killing big patches of it. This is just one example of the cascading effect we see and in fact, because coral reefs are so complex it’s very difficult to catalogue what additional changes have certainly taken place.

Challenges

Marine protected areas have no visible boundaries and can be challenging to enforce. It takes a cooperation between community members and stakeholders for MPA’s to have their biggest impact for protecting species.

Closing or restricting a fishery is a big deal and there have been many challenges and hurdles. Protected areas are a fairly recent experiment so the dynamics of how it might work were not then fully understood. The fishing community was not supportive of restricting fishing, likely because at the time it was first proposed it was a really radical idea and an unproven theory. It was a slow process and a true leap of faith but over time catch of other threatened species such as the Red Hind, also seasonally protected, steadily increased. This increase is linked directly to closures providing a safe space for reproduction. Fishermen who were once against establishing a protected area have become supportive of it.

Relationship building with local communities are essential for the success of fisheries closures and establishing protected areas. Fishers' lived experiences provide important context for decision-making and when protecting species is a shared goal, success is more easily attained. These partnerships also mean fishermen are more receptive to learning about the science and insights marine biologists can provide.

When the Nassau grouper population collapsed fishermen started targeting Red Hind which spawn in aggregations similar to Nassau. Now, with awareness and understanding of what happened to the Nassau population, fishermen were supportive of protecting the Hind spawning aggregation. This led to the establishment of the Red Hind Bank seasonal closed area in 1990 which was then became fully protected as the Marine Conservation District (MCD) in 1999. This management action with fisher support is significant because of its size (41 km2 or about 16 sq. mi.) and because it is an area permanently closed to fishing. The MCD is large enough that instead of just protecting a species, it is protecting an entire critical deep-water habitat, a truly novel concept for the Virgin Islands! No fishing or anchoring is permitted within the MCD. As a result, Red Hind are now more common and bigger than ever before at fish markets, restaurants, and the dinner table in the US Virgin Islands.

It Takes A Community

Illegal fishing trap buoys can be difficult to spot as they barely break the surface and could be painted in colors that match the sea. However, the buoys have one disadvantage on calm days: they can't hide between waves and are much easier to spot.

During a research excursion into the Marine Conservation District in February, 2023, Nemeth and his team happened upon a fish trap buoy. The MCD is approximately 10 miles offshore and very isolated so the only reason the tiny buoy was spotted in the midst of open endless waters was because they had incredibly calm seas and clear skies that day. Upon further investigation, six more buoys were found, all within the MCD. Even more alarming, the buoys were attached to string traps with up to 11 fish traps per buoy. Visualize if you will that the way these traps were designed and set create something of a landmine field that fish must navigate their way through before having the opportunity to reproduce. All told, the team estimated there were upwards of 60 traps, all set within the MCD.

The research team, being experienced certified technical divers, dove the traps located at depths up to 150’ to investigate. They found trapped inside were yellowfin Grouper, snappers, queen triggerfish, angelfish and many other species including the endangered Nassau Grouper. The location was recorded, photos taken for evidence and along with the identification of the trap owner, the violation was reported to enforcement authorities for follow-up.

The penalty for illegal fishing in the USVI is a fine of up to $10,000 and up to 60 days in jail per illegal specimen.

While we see increasing numbers, the Nassau Grouper population in the USVI is at a tipping point. The successful recovery of this species will not happen solely through governmental regulations and policing. It requires respectful partnership between legislators, fishers and community members.

Most Nassau Grouper will turn and swim away when approached. With no place to go, this grouper continued to stare at Kadison as she approached.

Many fishers are doing their part. In fact, some fishermen don’t even set traps outside the closed boundary in spawning season because they don’t want to accidentally catch Nassau. This is a very conscious and conservative approach to successful partnership. We also need more information to be shared about the Nassau grouper recovery so that recreational fishers will be aware that the Nassau grouper is a fully protected species and cannot be fished, speared or possessed.

With the remarkable increase in numbers of juvenile Nassau grouper, the USVI has an opportunity to be a model for other Caribbean nations who are experiencing the decline of this valuable species and others. Juvenile Nassau grouper also need to be protected from fishing as well as habitat degradation is that they too can migrate to the Grammanik Bank spawning aggregation site and contribute to future generations of juveniles. And, while not possible today, perhaps one day Nassau grouper populations will have recovered enough to be taken off the IUCN list and this conversation will simply be a footnote in history.

Learn more about Dr. Nemeth’s research here.

Despite the significant increase in Nassau Grouper this spawning aggregation has made, this is still only the beginning. What’s paramount is that this trend continues, which will only be possible through the collaborative efforts of scientists and fishers.